In this section: Management

Introduction to rabbit management

Pests are animals causing harm or significant disturbance in areas where they are not wanted. They often have the ability to flourish if left unmanaged in suitable environments. Physical, chemical and biological control options are available to variously cull, inhibit breeding or exclude pests from priority areas. It is rare that a single control measure will be completely successful. Even very effective biological controls require support from additional control measures.

Leading questions are:

Implement selected control options

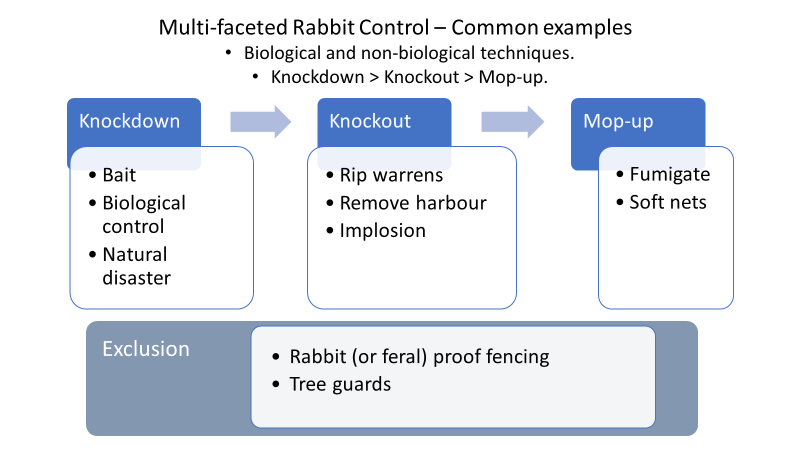

Rabbit control is best achieved from a well-timed combination of techniques to sequentially knockdown, knockout and mop-up pest populations. In some circumstances fencing rabbits out (rabbit-proof fencing or tree guards) may be an option. Williams & Moore (1995) provide an excellent discussion of the efficiency and effectiveness of different combinations of control options.

The humaneness of alternative rabbit controls has been assessed in accord with the Australian Animal Welfare Strategy. The results are available through pestSmart, along with a Code of Practice for the Humane Control of Rabbits. State based animal welfare and various heritage protection regulations may also be applicable.

In this section:

- Knockdown – culling to reduce numbers

- Knockout – inhibit breeding

- Mop-up – clean up and monitor

- Exclusion – keep rabbits out

Knockdown – culling to reduce numbers

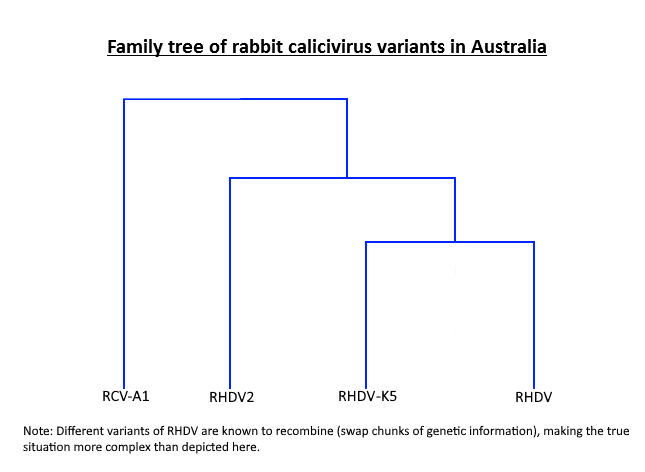

- Biocides. Three sorts of biological control are active in Australian landscapes; the viral myxomatosis and RHDV (calicivirus), and European rabbit fleas (introduced to help spread myxomatosis). RHDV-K5 is the only biocide currently available for active distribution by land managers. Biocontrols are inextricably linked to their hosts – if there are few rabbits around the bio-control agents will be less abundant as well. Yet there is a constant battle (‘arms race’) between rabbits and bio-controls as each evolves to their advantage. The influence of bio-controls therefore fluctuates with seasons, but they are an absolutely crucial foundation to ongoing rabbit control in Australia. See ‘Optimise biological controls’ below for more information.

- Baiting. The poisons 1080 and Pindone are registered for use against rabbits and the biocide RHDV-K5 is also available for release via ‘baiting’. State regulations and guidelines (e.g. precluding 1080 from use near dwellings or waterways) must be followed in the use of poisons for health and safety reasons and to reduce the risk of ‘off-target’ poisoning. Because rabbits are habitual feeders, it is recommended that a series of ‘free feeds’ are used before baiting, preferably along trails although bait-stations can be used. See ‘How to’ for more information.

‘How to’ information: Knockdown

More information: Optimise Biological controls.

|

RHDV-K5: Rule of Thumb RHDV bio-controls should not be released if green grass is present, because protein rich green grass stimulates breeding and young rabbits can develop life-long immunity to RHDV if infected when less than 8 weeks old . In much of Australia young rabbits can be expected to be present during July-December, hence the release of RHDV should only occur in drier months between January and June, if it is not present already. |

Knockout – Inhibit breeding

Warrens or protective harbour (like impenetrable vegetation or debri) provide protection for rabbits from the elements and predators and are crucial for the survival of young rabbits. Removing warrens severely reduces rabbit breeding and the likelihood of rabbits moving back into a cleared area from adjacent lands. Special techniques may be needed in sensitive sites of high social or environmental significance.

Whatever method is used to reduce the number of rabbits, unless efforts are made to destroy their warrens or harbour where they breed,

it will only be a matter of time until their numbers increase once again.

- Ripping. The aim of ripping is to destroy warrens and ensure they cannot be re-used by subsequent generations of rabbits. See ‘How to’ for more information.

- Implosion or explosion. Warren blasting may be used in areas inaccessible to ripping machinery. It is generally done by implosion (using ANFO – ammonium nitrate and fuel oil) rather than explosion, with the benefit of less disturbance to the land surface and less risk of subsequent erosion. Implosion uses lower amounts of explosive, so it is also a safer option for operators. See ‘How to’ for more information.

- Removal of weeds or debri. When rabbits live above ground under the shelter of vegetation or other debri, that cover is crucial to their survival. It provides shelter from predators and can give rabbits time to develop burrows. Removal is encouraged to reduce rabbit numbers and prevent reinfestation. Cleaning up may also serve as an important weed management or fire risk reduction exercise. See ‘How to’ for more information.

Where to find rabbits. Image: Darling Downs – Moreton Rabbit Board

‘How to’ information: Knockout.

- Overview of warren and harbour destruction, pestsmart

- Warren destruction by ripping, pestsmart

- Best Practice Rabbit Control, Step 2 – Ripping; VRAN

- Rabbit control in Victoria – Ripping

- Explosives – implosion or explosion, pestsmart

- Case study. Thackaringa station

- Case study. Arkaba station

Mop-up – Clean up and monitor.

Rabbit control is rarely completely effective. It is essential to chase ‘that last rabbit’ to reduce the risk of rebounding populations, and to continually monitor for remnant rabbits. A number of control techniques are suited to mop-up operations.

Fumigation can be an effective ‘mop-up’ technique.

- Fumigation. Rabbits in warrens may be treated by diffusion fumigation (when phosphine gas is released from aluminium phosphide tablets placed in burrows) or pressure fumigation (when noxious gasses are pumped into warrens). Fumigation is often used for ‘mopping up’ residual rabbits. Trained dogs may be used to help herd rabbits into their burrows, but not for catching or killing rabbits. See ‘How to’ for more information.

- Trapping. Soft nets, padded-jaw leg-hold traps or cages may be used for individual or small isolated pockets of rabbits, subject to any local animal welfare regulations. See ‘How to’ for more information.

- Shooting. Shooting may be used for residual or isolated rabbits, e.g. during a mop-up phase.

- Detector dogs. Well trained detector dogs may be used to locate hard to find warrens or isolated rabbits. Dogs are not to be used to chase down and kill rabbits. See ‘How to’ for more information.

- Ferrets. In difficult to access areas or urban and peri-urban areas when other measures are not feasible, ferrets are sometimes used to chase rabbits out of warrens into nets where they are euthanised. Ferrets that savage rabbits should not be used to flush rabbits from burrows.

- Quolls. After being declared extinct in the Australian mainland in the 1960’s eastern quolls are now being reintroduced to some reserves and conservation areas in south eastern Australia. One of the benefits of these natural predators is that they are adept at hunting rabbits in their burrows. Predation by quolls is thought to have been one reason for the failure of numerous early attempts to introduce rabbits to mainland Australia.

‘How to’ information: Mop-up.

A video overview of monitoring techniques is available from Monitoring Pest Animals.

Exclusion – keep rabbits out

In situations where other control options are problematic (small, semi-urban properties or highly valued environments for example), fencing rabbits out may be a practical long-term solution, provided that on-going monitoring and maintenance is kept up to ensure rabbits do not invade the fenced area. If rabbits are found, then ‘Mop-up’ control options could be used within fenced areas.

- Rabbit proof fencing. An important feature of rabbit-proof fencing is that netting is either laid on the ground or buried to prevent rabbits digging under the fence. A proviso is that rabbit-proof fences must be regularly inspected and repaired. Even then tenacious rabbits may still find a way through, under or over them, so monitoring inside fences for rabbits is also recommended. Rabbit-proof fences are part of regional rabbit control in parts of Queensland. See ‘How to’ for more information.

- Feral proof fencing. In areas with problems from various feral pests, it may be appropriate to consider fencing that prohibits more than rabbits. Fences to keep predators like cats and foxes out usually have a floppy top that folds back onto any climbing animals. See ‘How to’ for more information.

- Tree guards. Tree guards can provide a favourable micro-environment for seedlings, e.g. sheltering them from wind, as well as protecting them from grazing by rabbits. However, once the plants grow above the guard, they can be susceptible to nibbling by more adventurous rabbits. Larger, single trees can be protected by wire or steel mesh guards.

Tree-guards are not always effective against rabbits. Note the secateur-like damage to the young callitris by rabbits, far right. Images: Ron Sinclair & Bruce Munday.

‘How to’ information: Exclusion.

Follow-up: Monitor, Record and Respond

Follow-up, checking on the success of control efforts and responding immediately, should be factored into all control programs as part of monitoring and evaluation.

Monitoring. Information from monitoring should help reflective evaluation once a control program is completed, but it should also be an active part of all operations – checking to see they were effective and remedying any identified problems as soon as possible. Information, like rabbit or active warren numbers, should be available from before and after treatments. Examples include:

- Checking the effectiveness of a baiting program and relaying baits immediately if there was insufficient original uptake.

- Checking warrens after ripping to ensure no burrows have been re-opened and closing them immediately if they were.

Recording. Keeping a record of control actions (perhaps including a diary, notes, log-books, RabbitScan, and/or photos) avoids having to rely on memory, and makes review and evaluation much easier. It is the same as recording things like stock movements, fertiliser applications or irrigation on farms.

A number of tools are available to assist in data capture, information gathering and recording.

For more information about evaluation at the end of a control program, see Improve.

Useful Resources

Weblinks

Control techniques

- RabbitScan Handy Resources – Control tools

- Integrated rabbit control – AgVic

- The VRAN rabbit recipe – Monitor; then bait, rip, fumigate

- Western NSW Pest Chat: Rabbits – An introduction to all control options

- Understanding rabbit control options – Local Land Services

- Wool.Com/Rabbits – Control methods for woolgrowers (AWI)

- Pest management/Rabbits – Impacts and control methods (MLA)

- Moorabool Landcare Network – warren destruction videos

- Humane trapping – AgVic

Biological controls

- European rabbit. Biological control. – about myxomatosis and calicivirus

- Minimising RHDV infection in domestic rabbits – vaccination and other precautions

- Fifty-year review: European rabbit fleas – Spilopsyllus cuniculi enhanced the efficacy of myxomatosis for controlling Australian rabbits.’ Cooke BD (2022) Wildlife Research

Downloads

Comprehensive guides

- ‘Glovebox Guide for managing rabbits.’ (2020) Brown A, Cox T & Wishart JH. Centre for Invasive Species Solutions.

- ‘Managing Vertebrate Pests: Rabbits.’ (1995) Williams K, Parer I, Coman B, Burley J & Braysher M. Bureau of Resource Sciences & CSIRO Division of Wildlife & Ecology ResearchGate download

- ‘Rabbit Control. A guide for land managers’. (2008) Hunter C et.al. Dept of Primary Industries & Fisheries, Qld.

Control techniques

- ‘Conventional Rabbit Control: Costs and Tips.’ Hart Q. (2003) Bureau of Rural Sciences, AFFA

- ‘Rabbit’ Fact Sheet; Control techniques. (2021) Dept of Agriculture & Fisheries, Qld.

- ‘Rabbits and Destruction go Hand in Hand. Information Booklet for Land Managers.’ (2007) SA Murray-Darling Basin NRM Board.

- ‘Rabbit Management Guide’. Moorabool Landcare Group (Vic)

- ‘Improving the efficiency of rabbit eradications on islands. Workshop proceedings.’ (2010) Murphy E, Crowell M & Henderson W. Invasive Animals Co-operative Research Centre.

- ‘The rabbit and its control. Fact Sheet.’ (2008) Biosecurity Queensland.

- ‘Warren and harbour destruction’ (2012) PestSMART

- ‘Working with contractors for effective rabbit control.’ VRAN – Victorian Rabbit Action Network

Baiting

- ‘Bait delivery of RHDV-K5 – Standard Operating Procedures.’ pestSMART, Centre for Invasive Species Solutions.

- ‘Using RHDV for rabbit control. Fact Sheet.’ PestSmart

- ‘Releasing K5. A quick guide‘, PIRSA

- ‘Efficacy of Bait Stations for broadacre control of rabbits.’ (2001) Twigg LW, Lowe TJ & Martin GR. Department of Agriculture. WA.

- ‘First Aid. 1080 and your dog.’ Goh C & Lapidge S. Australian Wool Innovation

- Ground baiting of rabbits with pindone – Standard Operating Procedures’. Centre for Invasive Species Solutions.

- ‘Ground baiting of rabbits with 1080 – Standard Operating Procedures. Centre for Invasive Species Solutions.

- ‘Sodium Fluoroacetate – 1080 – Final Review Report & Regulatory Decision’. (2008) Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority.

- ‘1080: A weighty Ethical Issue’. (2020) Booth C. Invasive Species Council.

Exclusion fencing

- ‘Catalogue of fence designs’. Department of Agriculture, Water & the Environment, Australian Government.

- ‘Cost effective Feral Animal Exclusion Fencing for areas of High Conservation Value in Australia.’ (2004) Long K & Robley A. Arthur Rylah Institute, Dept of Sustainability & Environment, Victoria

- ‘Crop and Pasture Protection from Rabbits in Native Bush Remnants.’ (2002) Wheeler SH, Lowe TJ & Twigg LE. Department of Agriculture. WA

Small & peri-urban properties

- ‘Controlling rabbits on a small property’ (2019) South Coast NRM, Albany, WA.

- ‘Rabbit control for peri-urban landscapes.’ Murrindindi Shire, Victoria

- ‘Controlling rabbits in urban areas‘. Northern & Yorke Landscape Board

- ‘Rabbits: control in urban areas. Landcare Notes.’ (2000) Hay P. Department of Natural Resources and Environment, Victoria.