Understanding the biology of rabbits helps to identify opportunities for their control. They are social, territorial animals and able to breed prolifically.

In this section:

- Taxonomy – the rabbit family tree

- Physiology – unique features of rabbits

- Behaviour – social structures

- Breeding – reproduction

- Rabbit Diseases & Predation – health and survival risks, including viruses

Taxonomy – family ties.

Rabbits and hares are in the taxonomic order Lagomorpha, and make up the Leporidae family. There are over thirty species of wild rabbit, grouped into eleven genera (including Oryctolagus) that are native to various countries. There are no Leporidae native to Australia.

A number of rabbit species are endangered in their home country due to pressures from disease, predation and hunting, and habitat loss. Even though it is a serious pest in many countries, the European wild rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) is endangered in Portugal and Spain, an important part of its original domain (IUCN Red List).

Physiology

Rabbits weigh around 35 gm when born, and grow to 0.8 – 2.3 kg when mature. They have large, slightly protruding eyes to the side of their head, providing panoramic vision which, together with their large ears and good hearing, helps them detect predators.

Rabbits have a small mouth with unique upper teeth. They have a pair of long gnawing teeth (which grow continuously) and a pair of smaller teeth directly behind them, causing a distinctive 45-degree cut on grazed vegetation. Their small mouth enables them to be very selective in what they eat and to eat it to ground level. Rabbits will also dig for food, like roots or bulbs.

|

Signs of rabbit damage: Stripped bark and 45 degree bite marks on twigs. (Image: B Cooke) |

Rabbit gnawing on a rabbit carcass for sustenance during drought. (Image: G Schulz, NSW Govt) |

Rabbits eat up to a third of their body weight every day, selecting the most nutritious and palatable food available. Their preference is green grass and herbage (like seedlings and shoots), but they will eat seeds, roots and bulbs, and in times of drought even eat the bark from trees. As a general guide, twelve adult rabbits eat as much as one dry (i.e. non-lactating) sheep. See dry sheep equivalents link below for more information.

Rabbits exhibit caecotrophy – that is, they produce two kinds of faeces, some ‘hard’ containing fibrous plant matter and others which are ‘soft’ and contain finer particles. The soft pellets are produced during the day when rabbits are resting in their burrows. They are ingested directly from the anus, providing the rabbit with amino acids (produced by bacterial fermentation in the gut) and vitamins needed for good health. If prevented from eating their soft pellets they will suffer from poor nutrition and eventually die. Hard faecal pellets are produced when the rabbits are above ground.

In arid areas rabbits need access to water, but in other areas they get sufficient moisture from the food they eat.

Behaviour

Buck Heap. Rabbits mark their territory with dung heaps. (Image: SA Murray Darling NRM Board)

Rabbits are highly social and territorial. They typically form groups of about 5 adults (often 3 females and 2 males) and their immature young. They defend a territory centred on a warren which consists of numerous burrows, that may each be several metres deep and up to 45 metres long.

Burrows with more rabbits have more actively used (and hence bigger) entrances; burrow size indicates the relative size of rabbit populations. As a rule of thumb, each adult rabbit keeps two entrances looking well used, so if a warren has 10 active entrances there are about 5 adult rabbits living there. However, that simple relationship breaks down when there are lots of young rabbits about.

Rabbits defend their territory from other rabbits by fighting, but like cats and dogs, also use scent glands (including special chin and anal glands) to mark their territories. Male rabbits ‘chin’ other rabbits in their social group, and objects in their surrounds to make their territory smell familiar. They also leap high over other rabbits in their group and urinate on them for the same reason. Faeces, which smell strongly of anal gland secretions, are also deposited on dunghills (or ‘buck heaps’) to mark areas where rabbits commonly feed and to warn off strange rabbits.

Burrows provide protection from predators and the elements. However, where there is abundant surface cover, like thick scrub, bushes or debris, rabbits will live above ground. They prefer to feed within about 3-400 metres of their warren but venture much further when food or water is scarce. Rabbits are usually active from late afternoon until early morning, but they can be active anytime, especially when in high numbers. They tend to be less active on rainy or windy nights, when it would be harder for them to detect predators. Thumping of their hind feet is a warning signal to other rabbits.

Breeding

Rabbits can breed any time of the year, but conditions must be favourable. Good high-protein food must be available, and temperatures must not be excessive. In southern Australia breeding is typically from late autumn to spring when green herbage stimulates mating. High temperatures inhibit breeding and retard the survival of young. See ‘How seasons and diet stimulate breeding’ for more information.

During breeding seasons rabbits form social groups of 7-10 members, with a dominant buck (male) and doe (female). A breeding unit may include one to three males and over half a dozen females. A dominant male will mate with the more dominant females, while less dominant rabbits are likely to form pairs.

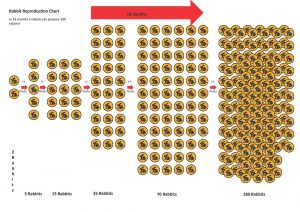

Rabbits are prolific breeders. They are sexually mature when 3-4 months old, gestation (pregnancy) lasts around a month, and litters contain from 4 – 8 young (kittens). Females can mate within hours of giving birth and can have 7 or 8 litters a year. In wetter, highly favourable areas a single doe can produce 50-60 offspring per year. In arid areas production of young is restricted but still between 16 – 20 young per year. In severe drought rabbits may produce only one litter, if they breed at all.

Young rabbits are reared in nesting burrows. (Source: CSIRO) |

The young are born in nests in the burrow or in a short, shallow, single entranced ‘breeding stop’. Young rabbits (from 20 – 60 days old) will disperse from warrens when there are too many rabbits present, relocating to warrens with lower densities. They may not move far, though movements of more than 20 kms have been recorded. Rabbits are more vulnerable to predation and environmental extremes when dispersing.

For more information on rabbit breeding and how, even though they live in small warren-bound groups, they avoid high levels of inbreeding, see ‘Avoidance of inbreeding’.

Mortality is high in young rabbits – up to 80% die before they are 3 months old, well before they are ready for breeding (at around 6 months or 1500 gm). However, given the high breeding rate, 85% mortality is needed to avoid a ten-fold population increase. The survival of individual rabbits may be due to their genetics, acquired immunity or seasonal factors like the abundance of diseases or insect vectors. Mapping their heritage and survival has reaffirmed the importance of small numbers of dominant rabbits and seasonal factors to breeding success. For more information see Former Research: Genomics of Resistance.

One rabbit can soon become many. Pedigree chart for a single male rabbit (3002), with progeny, apart from 2 on the left, from a single year. At least 8 survived to be recaptured when bigger than 500 gms. Blue lines = offspring from a male. Red lines = offspring from a female. (Source: Amy Iannella)

Rabbit Diseases & Predation

Rabbits are a prey species for numerous animals, sometimes as a preferred live food, sometimes as an occasional taking, or as carrion. Predators include:

- Mammals – e.g. foxes, cats, and dingoes

- Birds – e.g. wedge tailed eagles, some hawks, owls and ravens

- Reptiles – e.g. goannas and snakes (mainly for kittens)

It is unusual for prey species to control rabbit populations. Rabbits simply outbreed the pressure of predators in most situations in Australia. In cases where rabbits are an important part of the diet of a predator (as can be the case with feral cats) their abundance may help sustain predator populations. See Environmental Harm / Promoting Predators for more information.

Wild rabbits in Australia are subject to:

- Parasites – e.g. rabbit fleas and various internal worms

- Protozoal diseases – e.g. Eimeria and coccidia

- Viruses – e.g. Myxomatosis and rabbit haemorrhagic disease (RHD).

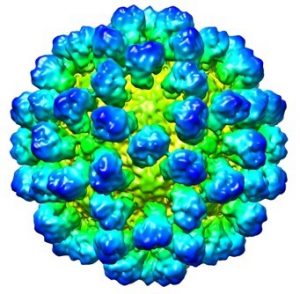

A number of the above are important in containing populations of European wild rabbits in Australia, especially viruses. The effectiveness of a disease is influenced by the characteristics of the disease, its transmission (e.g. by physical contact or via a vector like a fly, flea or mosquito), and the characteristics of the host or target organism, (e.g. if they have resistance or immunity).

Rabbit Hemorrhagic Disease Virus (RHDV virion. Source: Wikimedia Commons; A2-33)